AES 128 Padding Attack - CSACTF Crypto: Flag server

The challenge description is not really interesting, just a server to connect to and a python script:

And:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

import sys, time

from Crypto.Hash import SHA256

from Crypto.Cipher.AES import AESCipher

flag = "Flag goes here"

def encrypt(m):

key = SHA256.new(flag).digest()

try:

text = 'rowdy123' + m.decode('base64') + flag

except:

return "Opps, bad input"

pad = 16 - (len(text) % 16)

text += (chr(pad) * pad)

cipher = AESCipher(key).encrypt(text).encode("base64")

return cipher

print "State your name (in base64): "

m = raw_input()

print "Here's the package:"

print encrypt(m)

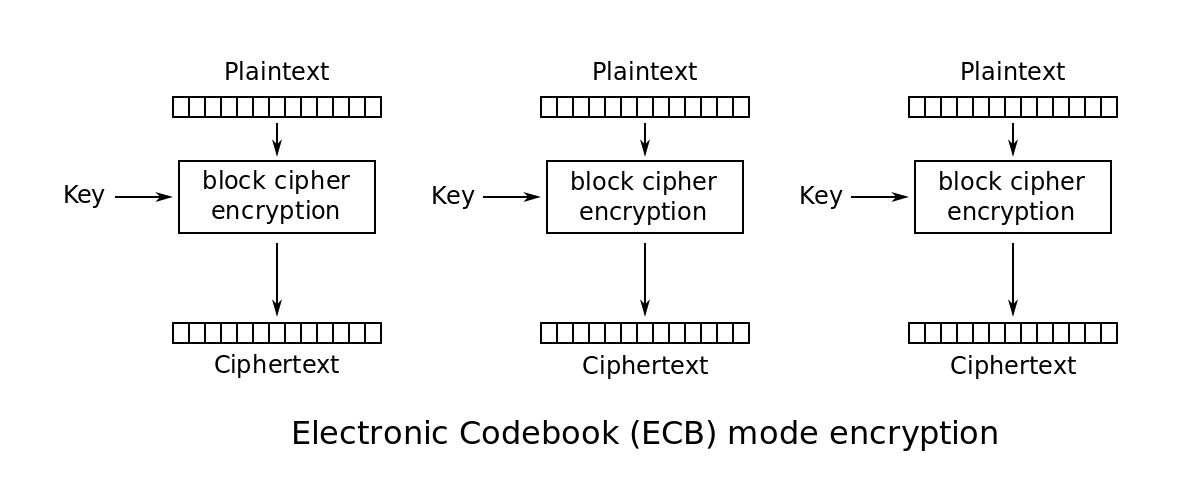

We can quickly see that the challenge will be about breaking AES, which, as mentioned in the documentation, uses ECB mode as the default mode if none were specified (our case).

AES in Electronic Code Book mode

[*] If you know how AES in ECB mode works, please feel free to move on to the next part, as here I’ll explain the basics of this method of encryption.

AES is an algorithm for block encryption that is comprised of different modes: ECB (Electronic Code Book), CBC (Cipher Block Chaining), CFB (Cipher FeedBack), OFB (Output FeedBack) and CTR (Counter). On this challenge we’ll be exploiting the simplest of all of them: ECB.

The way it works is by splitting the plaintext into chunks of 16 bytes, padding the last one if necessary so that they all have the same length. Once that is done, each chunk is separately encrypted with the same key, so that a ciphertext block is obtained. The image below illustrates the idea:

Now, the problem with this method of encryption is that it is deterministic: a given block of plaintext will always generate the same block of ciphertext. This fact, in combination with the fact that the attacker controls a part of the plaintext and that the algorithm pads the plaintext, leads to the possibility of guessing the remaining part of the plaintext, which is the flag.

Padding attack on AES

Theoretical example

Knowing how AES in ECB mode works and the fact that we can leverage the padding in order to recover the flag, it is easy to construct such an attack. Here’s an example that explains the concept:

- Let’s say the attacker controls the beginning of a plaintext that is going to get encrypted: input + secretValue.

- What can be done by the attacker is leverage this situation to align the bytes of the secretValue so that only one byte is in the first block and the others get encrypted in a different block. This method can be used to then recover one by one all the bytes by trial and error.

- What will be done is encrypt the message, which for the sake of simplicity it will consist of 4 bytes instead of 16, twice taking advantage of the padding. If we encrypt ‘000’ + secretValue, then the first block will consist of ‘AAAX’, where A will be our input and X will be the first unknown byte (A). Then, we need to save the ciphertext from this operation. Given the deterministic nature of the algorithm, we just need to repeat the operation, this time trying to guess the last byte (‘AAA’ + guess) until we get the same encrypted block. Once both ciphertexts are equal we will know that the first unknown byte is the byte we supplied, A.

- This will be repeated indefinitely until the secret value is obtained.

PoC in the server

This can be proved with the actual server, as we know the flag starts with CSACTF{. I will use Python’s pwntools in order to connect to the server and automate the whole process, as it’s rather tedious to do it by hand given that the input needs to be base64 encoded.

Here’s a simple script that will test whether the method works or not. What it will do is get the first encrypted block of two different plaintexts: rowdy1230000000 + flag and rowdy1230000000C + flag. As the flag starts with CSACTF{, the plaintexts become: rowdy1230000000CSACTF{...} and rowdy1230000000CCSACTF{...}. We can see that the first 16 bytes in both plaintexts are the same so this is the reason why the ciphertexts should be the same.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

from pwn import *

def main(input):

host = '34.74.132.34'

port = 1337

t = remote(host, port)

t.recvline()

input = base64.b64encode(input)

t.sendline(input)

a = t.recvall()

encoded = "".join(a.split("\n")[1])

hex = base64.b64decode(encoded).encode('hex')

return hex[:32]

if __name__ == '__main__':

print main("0"*7)

print main("0"*7 + "C")

And the output we get is the expected, the ciphers are the same:

1

2

3c621a1692811766512eec9aed651d44

3c621a1692811766512eec9aed651d44

Automating the solution

Once we know this works we just need to automate the process of checking through all possible characters. It is also necessary to check a different block of the ciphertext, as the previous method would only work with the first 7 characters of the flag. I decided to check the fourth block (bytes 96 to 128) in case the flag was lengthy.

The full Python solution is below:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

from pwn import *

def main(input):

host = '34.74.132.34'

port = 1337

t = remote(host, port)

t.recvline()

input = base64.b64encode(input)

t.sendline(input)

a = t.recvall()

encoded = "".join(a.split("\n")[1])

hex = base64.b64decode(encoded).encode('hex')

return hex[96:128]

if __name__ == '__main__':

flag = ""

while True:

# 55 because it's:

# + 8 bytes for the initial block

# + 16*3 for the three next blocks

# - 1 byte to brute-force the character

payload = "0"*(55-len(flag))

hex = main(payload)

for i in range(33, 125):

if main(payload + flag + chr(i)) == hex:

flag += chr(i)

print "Flag: ", flag

break

It takes a while to get the whole flag but in the end we get it! (I don’t know why but the final closing bracket wasn’t found)

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

Flag: C

Flag: CS

Flag: CSA

Flag: CSAC

Flag: CSACT

Flag: CSACTF

Flag: CSACTF{

Flag: CSACTF{s

Flag: CSACTF{se

Flag: CSACTF{ser

Flag: CSACTF{ser10us

Flag: CSACTF{ser10usl

Flag: CSACTF{ser10usly

Flag: CSACTF{ser10usly_

Flag: CSACTF{ser10usly_1

Flag: CSACTF{ser10usly_1_

Flag: CSACTF{ser10usly_1_d

Flag: CSACTF{ser10usly_1_d0

Flag: CSACTF{ser10usly_1_d0n

Flag: CSACTF{ser10usly_1_d0nt

Flag: CSACTF{ser10usly_1_d0nt_

Flag: CSACTF{ser10usly_1_d0nt_k

Flag: CSACTF{ser10usly_1_d0nt_kn

Flag: CSACTF{ser10usly_1_d0nt_kn0

Flag: CSACTF{ser10usly_1_d0nt_kn0w

Flag: CSACTF{ser10usly_1_d0nt_kn0w_

Flag: CSACTF{ser10usly_1_d0nt_kn0w_w

Flag: CSACTF{ser10usly_1_d0nt_kn0w_wh

Flag: CSACTF{ser10usly_1_d0nt_kn0w_wha

Flag: CSACTF{ser10usly_1_d0nt_kn0w_what

Flag: CSACTF{ser10usly_1_d0nt_kn0w_what_

Flag: CSACTF{ser10usly_1_d0nt_kn0w_what_t

Flag: CSACTF{ser10usly_1_d0nt_kn0w_what_t0

Flag: CSACTF{ser10usly_1_d0nt_kn0w_what_t0_

Flag: CSACTF{ser10usly_1_d0nt_kn0w_what_t0_p

Flag: CSACTF{ser10usly_1_d0nt_kn0w_what_t0_pu

Flag: CSACTF{ser10usly_1_d0nt_kn0w_what_t0_put

Flag: CSACTF{ser10usly_1_d0nt_kn0w_what_t0_put_

Flag: CSACTF{ser10usly_1_d0nt_kn0w_what_t0_put_h

Flag: CSACTF{ser10usly_1_d0nt_kn0w_what_t0_put_he

Flag: CSACTF{ser10usly_1_d0nt_kn0w_what_t0_put_her

Flag: CSACTF{ser10usly_1_d0nt_kn0w_what_t0_put_here

Flag: CSACTF{ser10usly_1_d0nt_kn0w_what_t0_put_here}

I hope you learned on this write-up! Ask me any questions if necessary!